Cover: Think globally, practice locally

How population health will improve health, reduce costs

Larry Wolk, MD, MSPH, Executive Director, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

As physicians, we spend much time with our patients treating diabetes, cardiovascular disease and mental health. But to really move the needle on such conditions, we need to invest at least as much time – if not more time – on the population-based practice of medicine, rather than merely treating individuals.

That’s why the concept of “population health” has gained support from the medical community in recent years. While population health has been given many definitions over the past two decades, I define it as any effort intended to impact the health of larger groups of people rather than one individual at a time. (Which, not coincidentally, is how I also define public health).

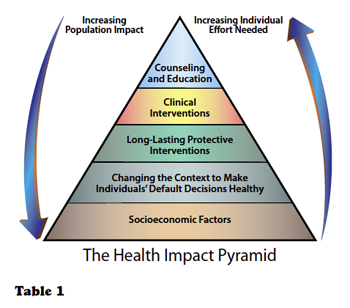

Advocates of population health include Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 2009. Four years ago, Frieden introduced a five-tiered pyramid to provide a framework to improve health on a population level (Table 1). At the base of this pyramid, indicating interventions with the greatest potential impact, are efforts to address socioeconomic determinants of health – the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age, as well as the systems put in place to deal with illness.

It’s hard to get your head wrapped around the idea of the social determinants of health unless you’ve practiced in a Third World country or an impoverished area that lacks the things that we take for granted – such as clean water, sanitation systems, clean air and safe food: the basic tenants for keeping a population healthy. By and large in Colorado, we take those things for granted unless somebody is worried about oil and gas operations polluting our air or drinking water.

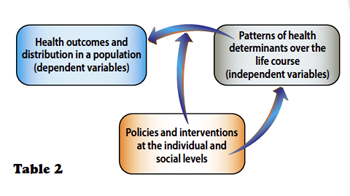

Population health addresses these and other environmental and social determinants by thinking outside the box to engage broader segments of the population to improve their health or influence public policy. (See sidebar: Population health in Colorado and Table 2). It is the natural progression of improving health and controlling costs that begins with the doctor-patient relationship, then advances to a specialized practice or medical home, then to a medical neighborhood, and ultimately to the general population.

While we have an important role in individual patient care, I would argue that many physicians don’t even think about or participate in population health-based activities. But doing so would make a significant and measurable difference to Coloradans, Americans and citizens worldwide.

Challenges and opportunities

Some physicians might say they lack the time and resources to engage in population health, but I would argue that the Affordable Care Act removes some of the financial barriers associated with the concept – creating new incentives and opportunities for getting on board.

Meanwhile, advancements in health information technology (HIT) are making population health practice more possible than ever before. In many cases, doctors are already putting the tenants of population health into practice without necessarily knowing they are doing so.

Prior to the ACA and environmental health issues aside, the role of public health was viewed narrowly as immunizations, promotion of family planning and chronic-disease prevention. Funding of public health initiatives was largely dependent on government entitlements and grants because there was no tangible return on investment.

Now, with the implementation of the ACA, that model is changing, with mandated health insurance, mandated preventive health benefits and substantially more people with coverage. Theoretically, if everybody is eligible for insurance, we shouldn’t need entitlements or grants for population-based health care services, including immunizations, family planning and/or cancer screenings.

I believe that such traditional public and population-health interventions should be shifted to the primary care settings or medical home settings. So, if population health is embraced by the entire medical sector, what is the role of public health? At the risk of sounding provocative, the role significantly changes, causing me to evaluate if and how public health departments should exist – regardless, from the patient and population perspective, even if the transfer of some of these interventions from public health to the health care delivery system were to occur, isn’t that a victory for everyone?

I’ve challenged our own state Department of Public Health as well our local public health authorities to shift the paradigm they operate under to the ACA and practice public health in the context of the evolving model of health care reform. I challenge the practicing community, physicians and hospitals to do the same by asking, “Can I address my population’s needs, given the new model of health care reform? In the extreme or ideal, primary care physicians may go so far as to say: “You know what? We don’t need public health to provide immunizations to our community. We are providing family planning services to our community. We are compensated and incentivized to provide population based services.”

Population health in Colorado

Population health may be a relatively new concept, but numerous programs and committed individuals are already at work in Colorado. Here are some things health professionals are doing throughout the state to make a difference on the health of large groups of people:

9HealthFair – Since 1987, this nonprofit program has promoted preventative health maintenance through free and low-cost awareness and educational screenings throughout metro Denver. With the support of 16,000 statewide volunteers and the promotional strength of NBC affiliate KUSA, the program has impacted more than 1.7 million individuals – earning endorsements from the Colorado Medical Society, the Colorado Nurses Association and the Colorado Hospital Association. With nearly 100,000 people taking advantage of the 9HealthFair every year, Colorado health professionals should be sure to support this program.

Colorado Diabetes Prevention Program – One of out three Coloradans are at risk of contracting diabetes. With support from the American Diabetes Association, Colorado’s Diabetes Prevention Program conducts tests to determine who is among that group with blood tests, counseling and education. Participants aim to lose 5-to-7 percent of their body weight by reducing fat and calories, and by being physically active for 150 minutes a week. This program deserves special accolades for taking what is normally done on an individual patient-to-doctor basis and applying it in a population-health context.

5th Gear for Kids – Led by James O. Hill, Ph.D., from CU’s Anschutz Health and Wellness Center, 5th Gear for Kids is a collaborative effort between the Aurora Public Schools and Cherry Creek School District. The program includes activities, events and incentives to encourage fifth graders to participate in healthy lifestyles. Participation is rewarded with prizes, free fitness classes, discounts on food, admission to local recreation centers, youth sports at the YMCA and more.

Walk with a Doc – Organized by Andrew M. Freeman, MD, FACC, FACP, a cardiologist at National Jewish Health, this program promotes physical activity while giving people a chance to walk or talk with a doc at a park at a regularly scheduled time. Participants range from people with serious health problems to those who live a sedentary lifestyle who want to start an exercise regimen. If more doctors throughout the state committed to taking routine walks with members of their communities, the entire population would benefit.

Public service – More physicians are seeking elected office because they see an opportunity to do something on a population level that they couldn’t do on a patient level. Sen. Irene Aquilar, MD, D-Denver, is a great example of someone who takes health-related issues and tries to do something on a population level that individual practices could never achieve on their own. Medical directors for health insurance companies also are in a position to impact population health in a big way since they could develop population-based programs for hundreds of thousands of people at once.

The reason public health departments offered immunizations was so that people without insurance could get their vaccines and avoid catching or spreading preventable diseases. For individual practices, immunizations could be an opportunity to get more people enrolled.

Case in point: Every physician has eligibility and billing systems that could be converted into enrollment systems with a little tweaking. Instead of turning somebody away who doesn’t have insurance, why not host a kiosk in your office where people can enroll and nobody is turned away due to lack of coverage? In essence, that’s population health. In fact, enrolling someone in a health insurance plan may do more to improve a patient’s health than an annual physical evaluation.

If that sounds daunting or even crazy, the good news is that many physicians are already participating in population health, providing preventive services, disease control and family planning. Addressing the social determinants, like insurance coverage, transportation, poverty and education may seem foreign but should be no less important and not that much more difficult to address, considering there are evolving models of payment reform that incorporate such activities.

Potential for the future

As CORHIO (Colorado Regional Health Information Organization) and QHN (Quality Health Network) make gains toward connecting all of Colorado to health information exchange (HIE), the potential for incorporating the principles of population health to the mainstream of health care grows by leaps and bounds. With CORHIO and QHN, physicians in the not-too-distant future can take a population-based approach to help an individual’s health – effectively addressing the needs of many while applying it in an individual fashion.

As a physician, this means when a patient comes to see me, much of what I need to know is right there in their electronic health record – a much better way to prevent duplication and focus more broadly on my patient’s health.

Currently, CORHIO and QHN are expanding and working on a direct exchange protocol – like a secure e-mail – that will enable doctors to access the kind of robust health information that helps Kaiser’s doctors use population-based clinical data to inform patients about best practices in treating conditions like diabetes or heart disease.

As these exchanges or repositories of individual patient information become more robust, the individual practicing physician will have more tools and reports available to better treat his or her population of patients. So as it relates to health information technology. In the spirit of population health, every physician should move to an electronic health record system, get connected to an HIE and plan to eventually analyze your own data to improve the health of your population. Meeting that challenge is easier and less expensive nowadays in large part because of the ACA.

Lastly, who can talk about population health and Colorado in the same breath without alluding to marijuana? With recreational cannabis now legal in the state, Colorado physicians may be uncomfortable talking about the pros and cons of consumption when the medical data hasn’t caught up. But population health leaves open the possibility that analytics can give physicians access to more information in the not-too-distant future. And whether it’s marijuana, or diabetes prevention or even the health effects of fracking – all issues that affect or are of interest to large populations – shouldn’t we as physicians make it a part of our roles to provide evidence-based information, whether in the office, our schools or other community settings?

I had an idea at one point in my career that every pediatrician should link to the school-based health centers in their communities. If that were to happen, pediatricians would be sought for education on health, participate in assemblies, teach classes and build that sense of community. As a health care professional, that demonstrates that I’ll see you when you’re sick, but I am also investing my time in keeping you healthy.

Up until now, there hasn’t been a financial incentive for physicians to participate in such activities, but with the ACA, you’re starting to see funding mechanisms emerge that will let physicians invest their time and be paid for that time. That will lead to better outcomes. And part of payment reform is not paying for each individual patient you see, but for the health of the patients and outcomes of patients you’re seeing.

It’s going to take us a while to get there, but for those of us who really “get it,” we’re not going to move the needle by exclusively providing individual patient visits – we’re going to do it by getting out there and improving the economic and social surroundings that our patients are living in as well as spending the time to invest in the communities where we work.

If physicians in Colorado and nationwide make population health a priority, actuarial knowledge will over time show that we are making good health sustainable and affordable for generations to come.

As a physician and director of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, I call on all of my peers to take steps to meet this challenge of bringing population health and community practice together – think globally!

Posted in: Colorado Medicine | Cover Story

Comments

Please sign in to view or post comments.