Cover: Controlling the cost curve: Looking to the consumer

Michele Lueck, President and CEO,

Colorado Health Institute

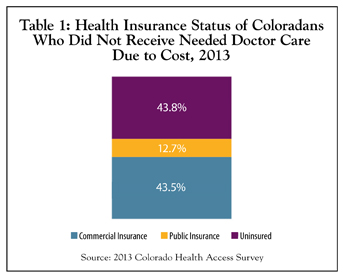

One of eight Coloradans has reported not getting medical care that they needed because it cost too much, according to the 2013 Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS). You might be tempted to think that most of the people going without care do not have health insurance. You would be about half right.

Of the Coloradans who said they didn’t get needed care from a doctor in the 12 months before the survey because they couldn’t afford it, about 44 percent were uninsured. A nearly identical percentage, however, had commercial insurance, most through an employer. The other 13 percent who didn’t get medical attention because of the cost were covered by public insurance, primarily Medicaid, Medicare and Child Health Plan Plus (CHP+).

Bottom line: An insurance card doesn’t guarantee access to affordable health care in Colorado. (Table 1).

At the Colorado Health Institute, we spend a lot of time thinking about the affordability of health care. The CHAS, which is funded by The Colorado Trust and which we field, analyze and disseminate, provides a wealth of data that allow us to delve into this crucial issue from a number of angles.

The Colorado Health Institute’s mission is to provide health care research and analysis that supports better-informed health policy discussions and decisions. But we go beyond the numbers to offer context and insight as well. It is clear that the continued growth of health care costs, even though the growth rate has slowed in recent years, is unsustainable, and that the ever-higher cost curve is compromising individual Coloradans, our state budget and the future of our health care system.

Across Colorado and the nation, smart and committed people are tackling the problem of spiraling medical costs. Many ideas are being tested and trials are being launched, ranging across a spectrum from free market solutions to regulatory interventions. We think that one promising strategy revolves around engaging and empowering consumers, a trend springing from market-based forces, technological innovations, and state and national health reform efforts, including the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Armed with more information, and motivated by stronger incentives to select care options that offer the best value, we expect to see an influx of consumers who are engaged in, and financially responsible for, their health care in ways that we haven’t seen in the past. They will shop for health care that offers better service and the highest quality at the lowest costs – and they will have the tools and the motivation to find all three.

They will be more than patients. Many of them will become true health care customers.

Looking ahead, we expect these newly empowered customers to join health care providers on the front lines for a sustained assault on health care costs.

The data: A view of the consumer

Understanding this expected wave of engaged and empowered health care customers begins with the data.

At the macro level, U.S. health care spending increased 3.7 percent to reach $2.8 trillion in 2012, with 17.2 percent of the economy devoted to health care. This is down a bit from 17.3 percent in 2011. There’s a bit of good news hidden in these big numbers, with 2012 representing the fourth consecutive year of slower growth. In total, between 2009 and 2011, the annual increase in national health care spending was the lowest in 50 years.

But health is a micro issue for most families. And health care is second only to food and housing when it comes to household expenses for services. This often means hard choices.

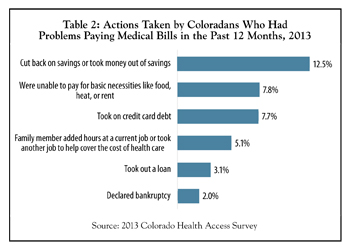

For example, medical bills left 8 percent of Coloradans unable to pay for such basic necessities as food, heat or rent, the CHAS found. Nearly 13 percent took on extra debt to cover health care bills and about 5 percent said a family member worked more hours or took another job. Two percent said they were forced to file for bankruptcy. (Table 2).

The most vulnerable Coloradans tend to be the most affected by unaffordable health care, the CHAS data show:

- Nearly 21 percent of blacks said they didn’t get needed care because it cost too much compared to 11 percent of whites and 13 percent of Hispanics.

- About one of five low-income Coloradans between 101 percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) didn’t get needed care compared to about 5 percent of those above 400 percent of FPL.

- Unemployed Coloradans were nearly twice as likely to have missed out on care as those with jobs.

- Education played a role, with about 23 percent of high school dropouts saying they didn’t get necessary care compared with 9.5 percent of college graduates.

Still, the CHAS shows that Coloradans across the spectrum of education, income and insurance are impacted by high health care costs. These data tell us that even as more Coloradans gain health insurance, either through Connect for Health Colorado or Medicaid, the issue of affordability will not go away. Indeed, if the health cost curve doesn’t bend significantly, the success of health reform will be imperiled.

The new health care customer

Competitive markets share certain conditions. Consumers bear the cost for what they consume. Both consumers and suppliers have complete and easy access to information in order to make choices. And barriers for new suppliers to enter the market are low or non-existent.

For a long time, these conditions did not describe the health care market. That is beginning to change.

First, health care consumers are paying more of their health care bills. The market-based theory is that consumers will make better choices, and forego unnecessary care, if they have a financial stake in the decision.

Insurance companies are adding plans with higher deductibles, higher co-pays, and higher co-insurance. More employers are opting to offer these types of plans. And more consumers are choosing them, many enticed by the lower premiums.

Colorado is proving to be a leader in this area. Colorado’s high-deductible plan enrollment reached 304,651 in January 2013, accounting for 8.4 percent of all private health insurance enrollment and placing Colorado in the top 12 states.

Nationally, out-of-pocket spending on health care grew 3.8 percent in 2012 to $328.2 billion, up from a 3.5 percent expansion in 2011, reflecting higher cost-sharing and increased enrollment in consumer-directed health plans.

Some economists point to the increase in high-deductible plans, and the resulting decisions by some households to scale back on visits to physicians, as part of the reason for the moderating growth in health care spending. Meanwhile, experts project $57 billion in annual savings if just half of the employees currently insured through their workplaces moved into high-deductible plans.

The question is if consumer cost-sharing will help to bend the cost curve in the long term. The answer, according to research, is that cost-sharing is a useful tool for slowing cost growth among healthy populations, but it is not as effective among unhealthy populations. In addition, there is concern – and some evidence – that consumers faced with more costs will cut back on all health care, including essential care and even preventive care that wouldn’t cost them anything.

Educating this newly-motivated consumer will be an important element in changing habits and saving costs.

The Colorado Health Institute is watching a number of other efforts with the potential to bend the cost curve, including private insurance exchanges, defined contribution health plans and reference pricing.

First, a quick rundown of defined contribution health plans and private exchanges.

A company with this type of plan gives each employee a fixed amount of money to spend on health insurance. The employee chooses the plan. If employees want a plan that costs more, they pay the difference. The strategy is to maintain employee choice, allowing them to be involved in choosing their health insurance and health care, while limiting the risk of increasing premiums for employers.

One way for employers to offer a defined contribution is through private insurance exchanges. These are usually on-line marketplaces established by large employers, where employees can comparison shop for various plans and purchase insurance using their employers’ contribution. Many companies see private exchanges as an emerging opportunity.

Taken to its logical conclusion, some experts predict that exchanges, coupled with defined contributions, will lead many employers to stop purchasing health insurance directly for their employees and instead help to offset the cost. This trend is likely to accelerate if both the public and private exchanges are working well and there are abundant choices.

Reference pricing, which counts on consumer involvement to help save costs, is gaining traction as well.

An insurance company sets a “reference” price it believes is reasonable for a specific medical procedure – a knee replacement, for example. If a consumer chooses to have this procedure from a provider who requires payment above the reference price, the consumer must pay the difference. It maintains consumer choice, while limiting the risk of insurers.

In one test by the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS), reference pricing saw the cost of hip and knee replacements decline by 19 percent. CalPERS permitted hospitals that allowed charges of no more than $30,000 for the procedures to join its plan. Those that didn’t agree to limit the charge to $30,000 were excluded.

Some potential problems may arise in implementation, however, including consumers who don’t know how much the reference price is – or how much the hospital is charging. Critics point to the arbitrary nature of choosing a reference price. Other experts say that reference pricing is a policy worth exploring. Transparent data as well as consumer education will be key to making reference pricing successful.

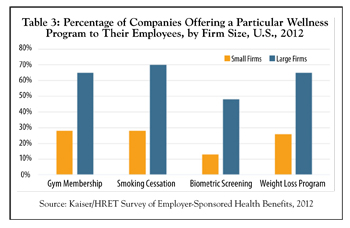

Finally, employer wellness programs are becoming increasingly popular. About half of the nation’s employers offer wellness promotion initiatives, and larger employers are more likely to have more complex wellness programs, according to a 2012 RAND Employer Survey conducted for the U.S. Department of Labor and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. About three of four employers offering a wellness program (72 percent) described it as a combination of screening activities and interventions.

But the RAND study found that, at this early point, the objective evidence doesn’t yet show significant cost savings or health outcome improvement. (Table 3).

Taken together, all of these efforts have one thing in common – an engaged and motivated customer.

Price transparency

Newly transparent insurance rates, a result of the ACA, have hit home in Colorado, which learned early this year that residents of Aspen, Vail and other mountain resort towns have the highest health insurance premiums in the nation.

This reflects, at least in part, an increase in overall health care costs in these areas. For example, in 2009 the per capita payments for health care services, paid for by both insurers and patients, were 36 percent higher in Summit County than in Denver County. By 2012, they were 61 percent higher. Professional costs were a large driver of the difference. They grew 45 percent in Summit County over this time, compared to a 9 percent growth rate in Denver.

These price variations have most likely been the case for a long time, but now people know about them. In response, Colorado Insurance Commissioner Marguerite Salazar has launched a study of the differences and potential state responses, another example of consumer power.

In order for patients to become true customers with the ability to shop for care, transparency will extend into the clinical world, where there is growing pressure to publicly reveal prices that are charged. The federal government has begun revealing how much Medicare pays individual physicians.

A study by University of Chicago researchers found that price transparency reduced the price charged for uncomplicated elective procedures by about 7 percent. The study revealed that most of the price reductions occurred in areas with intense competition among providers. Overall, the evidence points to a reduction in health care prices for patients with an incentive to consider costs, the authors said. While payers are almost never responsible for the full price charged, some regulators believe that price charged is a consistent way to compare ultimate expenditures.

A number of Colorado programs are providing tools to help customers make value-based choices. The Center for Improving Value in Health Care (CIVHC) has launched the web-based and searchable All Payer Claims Database. In June, a consumer portal is expected to be available in which consumers can compare what they are likely to spend for various services among different providers. Meanwhile, Engaged Public is leading an engaged benefit design pilot project that gives consumers more information and resources to make decisions about their care, with the goal of reducing the use of expensive but ineffective treatments.

Again, consumers are the common denominator in these efforts.

Technology

In many cases, shopping for health care is becoming as easy as clicking on the keys of a laptop.

About 45 percent of health care consumers report searching online for information about treatment options. By comparison, only 7 percent say they have used the internet to decide which hospital to visit. But around half reported they would like access to tools or websites that would let them compare costs of care, evaluate its quality and read user reviews.

Look to social media to make more inroads in health care, especially among younger consumers. About one of four respondents to the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions’ survey of U.S. adult health care consumers said they used social media for health-related purposes, mostly to learn about specific illnesses or health problems.

Still, physicians remain the most trusted source for reliable information at 44 percent. Independent health-related websites, such as WebMD, were trusted by 24 percent. Internet searches and social networking sites trailed far behind.

Forward-thinking clinicians are experimenting with adding social media to their customer toolkit. For example, the Mayo Clinic is a leader in this area, with a dozen blogs, more than 500,000 Facebook “likes,” more than 750,000 Twitter followers, 17,400 YouTube subscribers, 10,000 Pinterest followers and more than 1.4 million Google+ views.

The implications of these changes on costs have yet to be determined, but they hold promise.

Again, it’s all about turning a patient into a customer.

Conclusion

While engaging and empowering health care consumers is an attractive option to control costs, we need more information on how best to make this happen. Ideas must translate to action. And action must translate to effective cost reductions.

It will not be a quick or easy fix. A number of experts expect health costs to grow faster than inflation as the economy picks up steam and the pipeline of expensive technological advances continues unabated.

The Colorado Health Institute will be monitoring whether the patient-as-customer initiative actually bends the curve.

Michele Lueck has been president and CEO of the Colorado Health Institute since 2010. She is a veteran of the health industry and is leading a team that is providing evidence-based research and analysis for state health care leaders that is relevant and actionable.

Posted in: Colorado Medicine | Cover Story | Practice Evolution | Transparency

Comments

Please sign in to view or post comments.