Colorado Medical Society

http://dev.cms.org/articles/cover-mega-mergers-blocked/Cover: Mega mergers blocked

Monday, March 20, 2017 12:00 PM

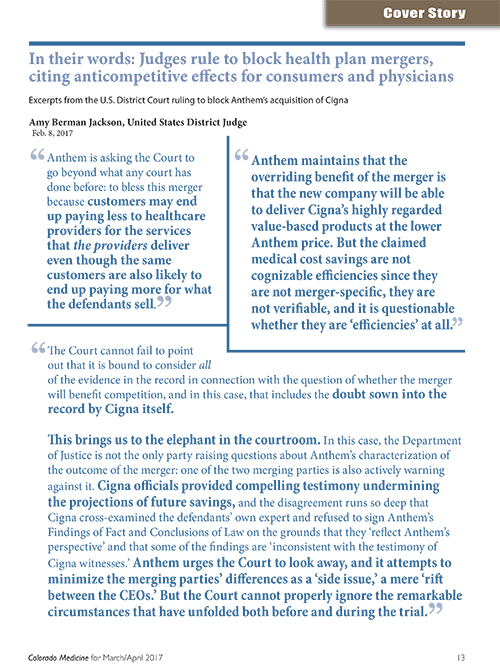

GRAPHIC - In their words: Judges rule to block health plan mergers, citing anticompetitive effects for consumers and physicians

In July 2015, the health care community was stunned when four of the five largest health insurers in the United States announced mergers. Anthem said it was acquiring Cigna, and Aetna claimed it would acquire Humana, thereby reducing the “Big Five” health insurers (that includes competitor UnitedHealthcare) to become the “Remaining Three.” Immediately, the American Medical Association, Colorado Medical Society and a number of other state societies mobilized to engage in what turned out to be more than an 18-month-long third-party advocacy campaign to stop the mergers before the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, state attorneys general, state insurance commissioners, Congress and now, in the U.S. Court of Appeals. Among the most prominent AMA partners in this effort was the Colorado Medical Society.

Health insurer markets require more, not less, competition

So why has this advocacy been important? The proposed mergers were occurring in markets where there had already been a near-total lapse of competition. Between 2006 and 2014, the national four firm concentration ratio (the collective market share of the four largest insurance carriers) increased from 74 percent to 83 percent. By comparison, the four firm concentration ratio for the airline industry – well known as a relatively concentrated sector – is 62 percent. Under the U.S. Department of Justice/Federal Trade Commission merger guidelines, the proposed mergers were presumed to enhance market power in a vast number of commercial and Medicare Advantage markets. The lost competition through the proposed mergers would likely have been permanent because of persisting high barriers to entry and health insurance markets. For consumers this would likely result in premium increases and a reduction in health plan quality. For physicians, the consolidation – and most especially the Anthem-Cigna merger – would result in lower reimbursements.

Should lower payments to physicians redeem an otherwise anticompetitive merger?

The ultimate objective of the antitrust laws is to protect consumer welfare. Thus, the question the American Medical Association and the Colorado Medical Society had to address to the satisfaction of state and federal antitrust enforcers – and they in turn would have to resolve to the satisfaction of a court – was whether the lower physician payments achievable in a merger are a consumer benefit that outweighs the lost competition resulting from the merger in health insurance markets.

As discussed below, this issue is being squarely addressed in the Anthem-Cigna merger that is now before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. What that court decides will have significant reimbursement ramifications for physicians, especially given the widespread perception within the health-insurer-financial-analyst community that health insurers are driven to merge for the purpose of gaining negotiating leverage over providers and thus a durable cost advantage over competitors. But before explaining the status of that strategy in the Anthem appeal, we turn to our successful antitrust challenge to the Aetna-Humana merger.

We can celebrate our successful challenge of the Aetna-Humana merger

On Jan. 23 of this year and following a 13-day trial, the District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that Aetna’s proposed acquisition of Humana violated the antitrust laws and accordingly, blocked the merger. The Aetna case is historic. It is one of only two antitrust health insurer merger cases that the Department of Justice has ever tried, the other being the Anthem-Cigna merger challenge. Soon after the Aetna court’s decision to block the merger, Aetna threw in the towel, deciding not to appeal and to pay Humana a $1 billion breakup fee pursuant to the merger agreement. Wall Street analysts now speculate that Humana could be a target for Cigna or Anthem, assuming for antitrust reasons they cannot close their own deal.

The absence of an appeal in Aetna-Humana – the first DOJ antitrust challenge to a health insurer merger ever tried – means that the precedent-setting antitrust opinion favoring the government and spanning 156 pages will not be disturbed. Thus we are better equipped to resist future mergers.

Are you an AMA member?

It is only through the support of our members that the AMA Advocacy Resource Center’s work as possible. Help sustain our state advocacy efforts on issues of importance to you and your patients. Join the AMA today ama-assn.org/membership

Why was challenging the Aetna-Humana merger important?

The blocking of the Aetna-Humana merger was a big deal, apart from the fact that the acquisition price was $34 billion. Had the government not won, the merger would have had dire consequences in Medicare Advantage (MA) markets. According to a recent Commonwealth Fund study, 97 percent of MA markets are highly concentrated and therefore are characterized by a lack of competition. The merger would have combined one of the two largest insurers of Medicare Advantage (Humana) with the fourth largest (Aetna) to form the largest MA insurer in the country. Aetna has been growing rapidly in Medicare Advantage. The merger would have ended the growing head-to-head competition between Aetna and Humana in a staggering number of MA markets. The government alleged that the merger violated antitrust law in the Medicare Advantage markets of 364 counties.

Aetna and Humana are also two of the largest insurers in the individual commercial insurance market on the public exchanges. At the time of the announced merger, Aetna sold insurance on the public exchanges in 15 states and had described itself as being “highly successful” in enrollment. The two companies compete head-to-head on the public exchanges in more than 100 counties.

What did the Aetna court decide?

The Aetna court concluded that the merger of Aetna and Humana would substantially lessen competition in all of the 364 counties the government alleged. It also rejected the health insurers’ arguments that federal regulation would likely be sufficient to prevent the merged firm from raising prices or reducing benefits. Nor, said the court, would entry by new competitors or a proposed divestiture to Molina suffice to replace competition eliminated by the merger. Finally, the court concluded the merger would be likely to substantially lessen competition on the public exchanges in three Florida counties. The court was unpersuaded that efficiencies generated by the merger would be sufficient to mitigate the anticompetitive effects for consumers in the challenged markets.

How is the Aetna precedent helpful in future physician challenges?

The significance of stopping the Aetna-Humana merger is measured not only in the competitive harm that was avoided but also in the precedent we helped establish. As challengers of health insurer mergers, AMA and CMS want the law to recognize narrowly defined product and geographic markets for health insurance where any given merger is more likely to be found to have a substantial impact. Health insurers, on the other hand, urge the notion that their products have multiple competing substitutes. Thus, in the Aetna-Humana merger, the two companies argued that their MA product competed with traditional Medicare.

We argued early on that traditional Medicare is no practical substitute for MA. Instead, we said that MA and traditional Medicare were separate products as evidenced by consumers of MA not readily switching to traditional Medicare, among other things. Thus, the reduction of competition in MA offerings caused by the merger would matter to consumers. To bolster this contention, we caused to be published on leading academic websites, and sent to the DOJ and state agencies, the opinion of 20 nationally renowned health economists attesting to MA being a separate product market. We also transmitted the economists’ expert opinion report to the antitrust staff of the attorney general (AG) of the state of Florida where Aetna and Humana have a huge presence. When the Florida AG (together with seven other states and the District of Columbia) and the DOJ (collectively, “the government”) later filed their lawsuit against the merger claiming that MA is a separate market, our efforts were richly rewarded.

However, the best was yet to come: In an extremely thorough opinion, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia agreed that MA is a separate market. Moreover, the relevant geographic market, the court said, was a county – a small area – and not, for example, statewide or the entire United States. The county is the relevant geographic market for MA because seniors may enroll only in MA plans offered in the county where they live. Thus, if Aetna were the sole MA insurer in Cook County, Ill., that fact would have profound antitrust consequences because a Medicare beneficiary could not turn to a plan offered in Broward County, Fla.

To summarize, now we have law defining a narrowly defined product market – Medicare Advantage – in a narrowly defined geographic area – a county. We therefore enjoy an improved likelihood of defending patient choice in MA from future mergers. Also benefiting are physicians who specialize in providing services to the elderly. With limited capacity to expand their business to traditional Medicare, these physicians are especially vulnerable given the exceptionally high degree of concentration in the MA market where the lack of competition enables insurers to depress the fees paid to physicians for services under MA.

Also helpful precedent in our expected future health insurer merger challenges is the court’s rejection of Aetna’s arguments that government regulation of MA and new market entry adequately protect consumers from a post-merger Aetna exercising its market power. AMA had encountered these defenses in every forum where the competition problems with the health insurer mergers were argued. According to the insurers, consumers are protected by state and federal regulatory structures – such as limits on medical loss ratios and state network adequacy standards – that are designed to deter and remedy anticompetitive harm, such that the benefit of antitrust enforcement would be small. Thanks to the Aetna case, there is now judicial precedent to the effect that such regulatory provisions are poor substitutes for the benefits of health insurer competition. Moreover the court found that there are high barriers to entry into MA markets and that the lost competition caused by the merger would be permanent. This is actually a universal characteristic of health insurance markets that AMA has had to argue in multiple federal and state forums. We now have the Aetna case to support the proposition of high barriers to entry into health insurance.

The government in Aetna also alleged that the effect of the merger would substantially lessen competition in 17 counties within the states of Florida, Georgia and Missouri. Here the market definition was undisputed. Aetna conceded that “on-exchange health plans” is a relevant product market and that each county is a separate geographic market. Hence, the relevant market was “public exchange markets in counties” – the kind of narrow market that again favors physicians in future health insurer merger challenges. But the wrinkle in the Aetna-Humana “on-exchange case” was that shortly after the complaint was filed, Aetna announced that it would no longer offer on-exchange plans for 2017 in any of the 17 counties where the government alleged the merger to be unlawful. Thus, Aetna said, the merger could not “lessen competition” within the meaning of antitrust laws, because there was no competition to begin with. To say that this defense backfired would be an understatement. The judge saw the withdrawal from the 17 counties not as a business decision, but instead as a follow through on the Aetna CEO’s threat to limit Aetna’s participation in the exchanges if DOJ brought an antitrust challenge. Moreover, Aetna documents and emails showed that Aetna withdrew from the 17 counties to evade judicial scrutiny of the proposed merger and to improve its litigation position.

The court further found that in three counties in Florida, the exchange markets were profitable for Aetna in 2015, and were projected to be also profitable in 2016. Therefore the court found that the proposed merger would likely cause a substantial lessening of competition in the on-exchange market within these three counties in Florida. Consequently, the court held the merger was unlawful in those markets, in addition to the markets in Medicare Advantage.

The Anthem-Cigna merger: Should it pass antitrust muster because it would lower physician fees?

We turn now to the Anthem-Cigna merger, a case where the last chapter has not been written because the case is now pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC circuit where oral argument is scheduled for March 24, 2017. Anthem and Cigna are the nation’s second and third largest medical health insurance carriers. The proposed merger would create the single largest seller of medical health care coverage to large commercial accounts, in a market in which there are only four national carriers still standing.

After a yearlong investigation and much CMS and AMA advocacy, the U.S. DOJ, 11 states (including Colorado), and the District of Columbia sued to stop the merger. The government argued that reducing the number of national carriers from four to three is significant. It would slow innovation and result in higher premiums. Unlike other insurers, Cigna relies on innovation to compete, and its value-based care strategies have spurred Anthem and other insurers to improve their own products. Moreover, the government argued, Anthem’s efforts to require Anthem network providers to apply Anthem’s lower rates to Cigna patients would erode Cigna’s relationships with its providers – relationships that are fundamental to Cigna’s capacity to innovate.

The court issued a 140-page opinion agreeing with the government’s contentions. It concluded that the merger should be enjoined because of its anticompetitive impact in the market for the sale of health insurance to “national accounts” – customers with more than 5,000 employees, usually spread over at least two states – within the 14 states where Anthem operates as the Blue Cross Blue Shield licensee. The court further found that the proposed acquisition would also have an anticompetitive effect in the market for the sale of health insurance to large groups in Richmond, Va. Because these violations were sufficient to block the merger, the court found it unnecessary to decide whether the merger would also harm competition in the market for the purchase of health care services from physicians and hospitals in 35 separate local regions within the Anthem states.

In finding an antitrust violation, the court rejected Anthem’s central defense: that the merger would allow it to extract lower reimbursement rates from doctors and hospitals and pass those savings on. Anthem claimed that it would achieve these “savings” by offering “the Cigna product at a lower Anthem price” through contractually forcing providers to extend the fee schedules that Anthem has already secured. The trial court however found that the Cigna model depends upon collaboration that requires a higher level of compensation. Cigna’s collaborative arrangements, said the court, are aimed at lowering utilization and thus are central to the value-based approached and medical cost trend guarantees that Cigna is selling.

The Anthem trial court’s decision is a stunning affirmation of the position urged by AMA and CMS. The judge determined that forcing fees lower would not benefit consumers and “would erode the relationship between insurers and providers” and “reduce the collaboration” that is essential to innovation in payment and delivery. The court found that “effective collaboration requires more of the physicians and hospitals, and they expect to be paid for it…” Moreover, the court noted that rather than passing along lower reimbursements to consumers, Anthem’s own documents revealed that the firm had considered a number of ways to capture the network savings for itself and not pass them through to the customers – a finding that buttresses one of AMA’s principal contentions in opposing the merger.

Insurer merger agreements to depress physician fees are not efficiency producing

The Anthem court noted that there was no basis for concluding that provider fees were “excessive.” A merger agreement to depress physician fees, the judge reasoned, is not efficiency producing, and better characterized as an exercise of buyer power:

“[S]ince Anthem’s efficiencies defense is based not on any economies of scale, reduced transaction costs, or production efficiencies that will be achieved by either the carriers or the providers due to the combination of the two enterprises, but rather on Anthem’s ability to exercise the muscle it has already obtained by virtue of its size, with no corresponding increase in value or output, the scenario seems better characterized as an application of market power rather than a cognizable beneficial effect of the merger.”

The Anthem case goes to the court of appeals

Anthem has appealed and has asked for an expedited decision so that it can meet the merger agreement closing deadline of April 30 when Cigna, which no longer wants to merge, can walk away from the agreement and ask for its breakup fee of $1.8 billion. In its appeal, Anthem does not dispute that the merger would be anticompetitive in a national accounts market but for claimed savings. The savings, Anthem says, would come from applying Anthem’s lower reimbursement rates to Cigna physician and hospital contracts, thereby reducing their payments by billions of dollars. Employers and employees would be the beneficiaries, given the automatic pass-through of health care costs under the ubiquitous administrative services only (ASO) contracting in the national accounts market.

The foundation of Anthem’s appeal is its centerpiece argument, rejected by the trial court, that a merged company would supply a Cigna-quality product at Anthem’s lower provider price, and that this represents an increase in “consumer welfare” that outweighs the distortions to the health insurance market that the merger would cause. Supporting Anthem is a brief filed by seven individual economists and business professors arguing that the district court erred by considering only the consumer harm of potential premium increases while disregarding the consumer benefit of potential provider price reductions. The government, of course, is contesting the appeal, notwithstanding Anthem’s representation, in a Delaware state court proceeding, that a settlement is at hand because of new Trump-administration Justice Department leadership and Vice President Mike Pence’s favorable view of Anthem. Filing amicus briefs supporting the government are the AMA, AHA and, at AMA’s suggestion, 27 professors who have expertise in the subjects of health economics, antitrust and/or competition policy. (See more information in the sidebar.)

The professors are from leading academic centers and many are nationally renowned. They argue that although greater insurance market concentration tends to lower provider prices, there is no evidence the cost savings are passed through to consumers in the form of lower premiums. To the contrary, they observe, premiums tend to rise with increased insurer concentration. In addition, the scholars agree with the Anthem trial court’s skepticism that the largest source of alleged merger-induced cost savings – a reduction in rates paid to providers – will be beneficial to consumers, let alone sufficient to offset the harm arising from reduced competition in insurance markets.

AMA’s amicus brief reflects the many months that the AMA and Colorado Medical Society spent analyzing the likely effects that an Anthem-Cigna merger would have on the physician marketplace. AMA argues in the Anthem appeal that even if Anthem were to give its customers all the savings from forcing physicians to lower their fees, the resulting social harm from lower quantity and quality in the market for health care services would undermine the benefit of these savings. Anthem has never explained how the merged company could force Anthem’s providers to participate in Cigna’s resource-intensive programs without an increase in compensation, or how it could force Cigna’s providers to continue to offer those programs for less compensation. Instead, imposing Anthem’s lower rates on providers – now reimbursed at Cigna’s higher rates – would destroy consumer welfare by undermining the collaborative relationships with providers for which Cigna is known, ultimately reducing the quality of the product.

The quality concerns expressed in AMA’s appellate brief echo CMS physician survey findings

The quality concerns expressed in AMA’s amicus brief echo what the Colorado Medical Society prominently learned when it canvassed its members about the likely effects of an Anthem-Cigna merger. Of the nearly 600 Colorado physicians who fully responded to a CMS survey, 72 percent said that it was very likely or somewhat likely that reimbursement rates for physicians would decrease; 66 percent expected reduced collaboration in patient care from providers; 62 percent said that physicians would be forced to spend less time with patients; and 58 percent said that they would reduce investments in practice infrastructure. Surveys in other states found similar results.

In its appellate court brief, AMA also expresses concern about the long-term effect on the medical profession and consumers. The district court found no evidence that the rates charged by providers within Anthem’s service area are “inflated due to the providers’ market power.” Therefore, reducing reimbursement to physicians will likely reduce patient care and access by motivating physicians to retire early or seek opportunities outside of medicine that are more rewarding, financially or otherwise. A recent survey by The Physicians Foundation shows that 48 percent of physicians plan to cut back on hours, retire, take a non-clinical job, switch to “concierge” medicine, or take other steps limiting patient access to their practices. According to a study released by the Association of American Medical Colleges, the U.S. will face a shortage of between 61,700 and 94,700 physicians by 2025. An Anthem-Cigna merger threatens to swell these figures; the CMS survey of Colorado physicians found that 13 percent believe that if they are not able to contract with a merged Anthem and Cigna, they will have to close their practices. Given that there are already too few physicians, it will not enhance consumer welfare to drive down reimbursements so far that physicians are driven from the practice of medicine.

The findings of the American Medical Association, says the AMA in its brief, are consistent with the conclusions of academics and consumer advocates who have examined the proposed merger. Professor Leemore Dafny, a Harvard economist who focuses on the health care industry, testified to the Senate:

“[E]ven if price reductions [for health care services] are in fact realized and passed through [to consumers], if they are achieved as a result of monopsonization of health care service markets then consumers may experience an offsetting harm. Monopsony is the mirror image of monopoly; lower input prices are achieved by reducing the quantity or quality of services below the level that is socially optimal.”

At the same hearing, the senior policy counsel of Consumers Union testified that “a dominant insurer could force doctors and hospitals to go beyond trimming costs, to cut costs so far that it begins to degrade the care and service they provide below what consumers value and need.”

The AMA brief concludes with the observations of the California Department of Insurance when it recommended that the United States challenge the merger: “Allowing Anthem to increase its already enormous bargaining power will further limit network size and excessively squeeze reimbursement rates, thereby discouraging provider contracting and unacceptably reducing consumer choice and quality of care.” The Department of Insurance also pointed out that it had discovered that Anthem violated laws regarding claims handling 16,000 times, and that the California Department of Managed Health Care ranked Anthem third worst among 10 companies on “coordination of care.” Describing a merger between UnitedHealthcare and PacifiCare in 2005, the Department of Insurance noted that while the combined company met its cost-cutting goals, it did so at the expense of quality and service; after the merger, PacifiCare violated the insurance laws more than 900,000 times.

Conclusion

Hopefully the Court of Appeals in Anthem will preserve the vital district court’s conclusion that an enhanced ability to coerce physicians to accept lower reimbursement is no merger efficiency defense. Such a decision would raise this principle to the authority status of a DC Court of Appeals decision, a court widely regarded as having prestige second only to that of the Supreme Court of the United States.